Seeing Past the Windshield

The winter after our second child was born was a challenging one for our family. We had naively imagined that after my husband completed his master’s degree, our greatest difficulty would lie in choosing between job offers. The job offers didn’t materialize. Instead, we found ourselves back in our home city, where my husband cobbled together a couple of low-paying jobs into a six-day work week that provided something of a livable income for our family of four. We had one car, and a workplace that was impossible to reach by transit, so Andrew took the car five days a week, and I stayed home with the kids. Once a week, I would load up the kids in the car and drive him to work so that I could go shopping. Depending on traffic, those trips to drop him off and pick him up at the end of the day amounted to two or three hours in the car with a toddler and a baby who didn’t take well to the car seat, which is why I only did it once a week.

Over and above looking back with a fascinated shudder and wondering, “How did I survive that year?”, two memories of that drive are burned into my mind. Once, after dropping Andrew off on a snowy day, I hit the brakes at an intersection, skidded, and spun nearly 180 degrees. How I managed to avoid colliding with anything on that crowded road, I can only chalk up to a host of burly guardian angels. I sat there stunned, staring straight into the oncoming traffic, acutely aware of my two children in the back seat (unharmed, thank heavens!) until a nice man knocked on my window and offered to drive my car into an adjacent parking lot, where I took deep breaths, collected myself, and then miraculously got back into traffic and drove my babies home.

The second memory also involves a blizzard. We were on our way home, and Andrew was in the passenger seat. We were on the freeway in rush hour, the sun was going down as fast as the snow was falling, and my windshield wipers weren’t keeping up. Ice was accumulating on the windshield, and I couldn’t see the road. I was conscious of nothing but my two babies in the back of the car, and that ice obstructing my vision.

“I can’t see where I’m going,” I yelped.

“You can see through the ice,” my husband insisted. I thought he was crazy. I was driving blind.

“Here,“ he said as I continued to complain, “Pull over and let me drive.”

Stopping on Deerfoot Trail in low-visibility conditions isn’t the safest thing to do, but it was our only option that day, so I moved over to the shoulder and changed seats with him. He calmly pulled back into the long line of slow traffic and continued our journey.

As I relaxed a little in the passenger seat, something amazing happened: I found I could see through the ice. The view was a little distorted, but it was there. All I had to do was shift my focus from the ice six inches from my face to the road in front of it. I had simply been looking at the ice instead of looking at the road!

By the time we reached our apartment, I realized I had just experienced a great life lesson:

Don’t get so caught up in the obstructions immediately in front of you that you fail to focus on where you are going.

Like most great life lessons, it’s easier said than done.

Once I had a three-year-old. At church, three was the age that a child graduated from Nursery and began attending Primary. We had hyped up this transition for weeks, but on that first Sunday in January, it took my child all of ten minutes to realize that Primary wasn’t really about being a Big Kid. It was about sitting in a chair for a Long Time. They stood up, turned around to find me sitting at the piano, and announced, “Mom, I’m bored.” After that, they cried every time we brought them to Primary. For a whole year. Unfortunately, Primary wasn’t optional, because my husband was teaching a Primary class, and I was the Primary pianist. We weren’t available to take them somewhere else during that time.

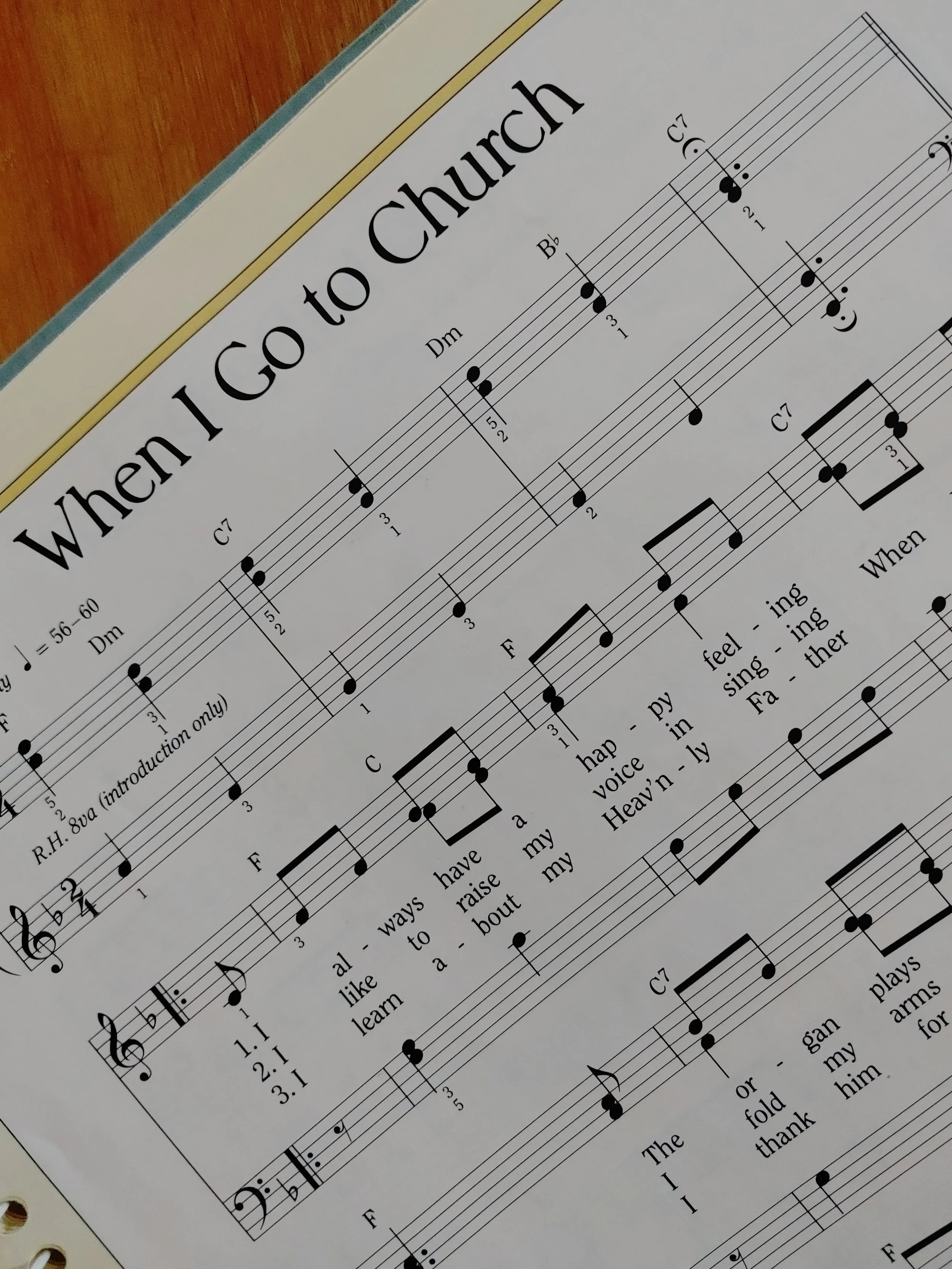

We used to sing songs while driving to church. (It prevented the kids from killing each other.) One morning, I told my three-year-old, “It’s your turn to pick a song.”

“Okay,” they said, “Let’s sing ‘I Always Have a Happy Feeling When I Go to Church.’ Only, you sing and I’ll be quiet, cuz I don’t have a happy feeling when I go to church.”

Ouch!

In the meantime, I kept praying. If God wanted me to play the piano for Primary, then I needed his help: “Please tell me how to help this child to be happy in Primary.” And I got an answer, but not the answer I was looking for. Every time I prayed, I was filled with an overwhelming sense of love for my child. That was all. So I just kept loving them. The Primary class was the ice on the windshield. Love, and our relationship, was the road.

Eventually, they had to call another Primary worker whose only job was to take my child into an empty classroom and play with them through Primary. Eventually my three-year-old turned four and learned to sit on a chair (some of the time.) Eventually, they grew up and went to university and sat through whole lectures without crying. And we still love each other.

I think I got that life lesson. I’m still working on the next one.

My adult children struggle with a basketful of mental health issues: depression, anxiety, ADHD, autism spectrum disorder. And I hate it. I hate seeing them suffer. I hate the way these issues block their amazing potential. I hate that I couldn’t find a way to raise them that prevented these things. I hate not having a way to fix them now.

It does occur to me, from time to time, that I may be looking at the ice, instead of the road. It’s natural to want my children to be perfectly happy now, to have notable careers and perfect relationships, to be wise, resilient individuals who have a positive impact on the world around them. But is it possible that their mental health obstacles are actually helping them become the best people they can be? That suffering is making them more empathetic, more wise? That the emotional strength they exercise while struggling to function in spite of quirky brains is greater than the strength they would develop doing things perfectly in a perfect world? Isn’t it possible that their mental health issues are the ice, and the shaping of their characters is the road? That God has a plan for them that includes mental health challenges?

I can’t tell you I’m perfectly convinced of any of this. I still hate to see them suffer; I still occasionally waste time wondering what could have gone better during their childhoods; I’m never going to stop praying and working for healing for each of them. But when I look past the ice of their current struggles to the long road - who God wants them to become eternally - it gives me hope. They are shining spirits making incremental, day-to-day progress in imperfect bodies. And that gives me hope.